For Part One of this series go here:

Part Two

The headwaters of the Green River originate high in the Wind River mountain range in northwestern Wyoming. Much of the range is on a Native American reservation. I have backpacked in the Winds (with Denis, of course) and it is some of the most rugged, most remote territory in the lower 48. The fishing is spectacular. Abundant snows in the winter begin to melt in the spring which drain into streams which form the Green – ice-cold, crystal clear and sweet – a far cry from the murky waters we canoed in southeastern Utah.

The Noxious Plant

There isn’t really anything in nature I hate. Mosquitoes? I can deal with them. Horseflies? They suck but there are ways to mitigate them. Poison ivy, spiders, snakes? Meh. I must admit, I will probably ask God why he created rats, but I don’t hate them.

But there is a plant I simply detest. It’s called tamarisk, also known as saltcedar. Native to Eurasia, the plant was imported to America where it was planted along small parts of the Green for erosion control. Big Mistake! Unintended consequences! With no natural enemies, the tamarisk aggressively took over both banks of the Green and Colorado rivers, choking off the natural grasses, cottonwoods and willows that formerly graced the riverbanks. Tamarisk provides lousy habitat for birds and wildlife, and alters the pH of the riverbank soil. The plant grows as a tall, dense woody bush up to twenty-five feet high and is, for all intents and purposes, impenetrable. Worst of all, it is an extremely thirsty beast. It is estimated that if the tamarisk had not contaminated the rivers, the Colorado and its main tributary the Green would carry enough additional water for twenty million people per year! Lake Powell and Lake Mead would be consistently full. For canoeists and rafters, the tamarisk provides a clear and present danger: the plant is so thick and impenetrable that if trouble occurs, the tamarisk effectively prevents the canoeist from exiting the river unless he/she is fortunate to find one of the extremely rare clearings where campsites exist. The tamarisk multiplies the danger of the river significantly.

Back to our intrepid fourteen canoeists. The first night as we were relaxing at our campsite, Rock Thompson indicated he could get a weather report via text from some satellite device he had installed if his wife or son sent it to him. They both did. The report could be summed up in four words: hot with heavy winds.

Winds are the bane of almost all outdoor sports and activities, but especially water sports like canoeing, rafting or boating. Unlike on land, where wind impacts, say, your golf ball, it doesn’t impact solid ground like the fairway. On the water, however, the wind not only pushes around your boat, but it also pushes around the surface on which the boat travels in the form of waves. Upon hearing the next day’s forecast, we resolved to get an early start before the winds kicked up in the afternoon.

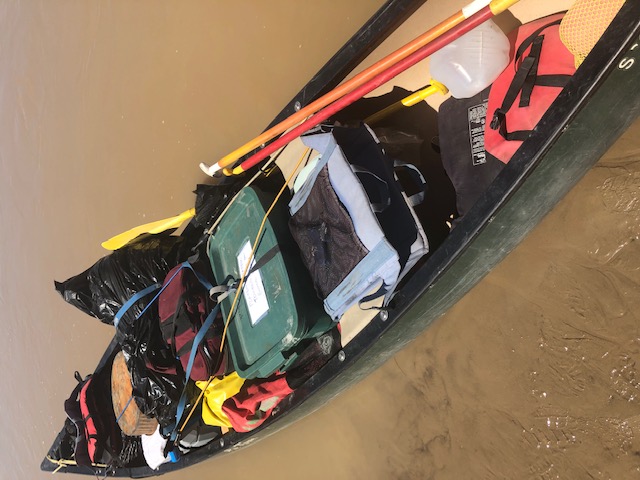

The second day, of course, we were still loaded to the gills with seven more days of food, fuel, beer and water (we brought in about six gallons of water per person).

The Green is one big, powerful and deep river by western standards. It’s the 15th longest river in the US. Along the course we traveled, the river averaged about 150 to 250 yards wide and 20 feet deep. When we started our trip the river was flowing about 13,000 cf/s, more than twice its yearly average, the current a little more than 4 mph.

If you note in the accompanying map, you will see that our overall direction was south/SW. Which was exactly in the face of a 25-30 mph wind with gusts up to 40. Just like a sustained uphill will string out cyclists or runners, a strong steady headwind spread out our canoes, with the stronger, more experienced members pulling ahead.

Chalmers and I were in the sixth canoe. It was about noon, I believe, when we heard shouts from behind us. About sixty yards to our rear, we saw Pat and Becky in the water, their canoe capsized. Oh no! We shouted ahead for Denis, who was in the canoe with Jayson and finally alerted them that Becky and Pat were in serious trouble. Chalmers and I considered trying to turn upstream to help, but in the wind, we couldn’t risk turning our canoe broadside. So we made our way to the bank, where we latched onto some tamarisk to hold us until Becky and Pat passed us. They were hanging for dear life to the canoe, Becky clutching to her paddle. We didn’t know this at the time, but the bow rope had entangled her legs.

By this time Denis and Jayson were in full rescue mode. They too had slowed their canoe with the tamarisk and allowed Pat and Becky’s canoe to pass. Once past their position, Denis and Jayson paddled alongsige and located a rope, but they were unable to get the capsized canoe to the bank. The damned tamarisk! We must have floated another mile or so without a spot to bring the capsized canoe to shore when Denis began to worry. “We’ve got to get them out of the water,” he said with exasperation and concern in his voice. Finally, there was a little cove where we could get Becky and Pat’s canoe near enough to the bank where they could finally get mostly out of the water. Their canoe was now roped to Chalmers and mine and I was able to tie off to some tamarisk. Becky and Pat were visibly shivering, and they were in shade and water above the knee. Still really cold.

Getting Pat and Becky’s canoe river-worthy once more was a long and difficult process. Thank God Denis’s engineering mind was there to figure out the logistics. All the gear was roped in, so Denis had to cut the rope to free a piece of gear, send the gear to Pat where Pat would stow the gear in the tamarisk, and then tie off the remaining gear to keep it from floating down the river. And then repeat the process.

We ran into a little good luck. A raft manned by a young family, Joe and Christine and two pre-teen children, moored alongside us and did what they could to help. We had met them the evening before. But just the fact they were there heartened us in a significant way. Denis and Pat finally got all the gear to the bank, and we eventually got the capsized canoe upright, although full of water. Denis, Jayson, Joe, and Chalmers bailed the water from the boat. Gear was repacked, and Pat and Becky gingerly boarded the canoe and we were once again on the river. (But not for long.) By my reckoning, Becky and Pat were in the water about forty-five minutes and it took us another two hours to restore their canoe, so we were hours behind the four canoes which made up the rest of the party.

The weather had not improved at all once we were back on the river. Chalmers and I struggled to maintain control of our canoe. It was my turn to organize lunch, so I removed the pulled pork from the cooler and set it on the bow to warm up in the sun. I didn’t like being ahead of Becky and Pat in case they had additional problems. Chalmers and I started to head toward the bank when we were hit by a gust and then a wave broadsided us. “Bob! Bob!” shouted Chalmers. I frantically tried to force the bow into the wind, but it was too late. The canoe had taken too much water, and in seconds we were totally swamped. I was still seated in the canoe but water covered me up to the neck. I yelled to Jayson who was nearby to scoop up the pulled pork (he couldn’t).

My mind was racing with emotions. I felt little fear but considerable dismay. A dry box had opened and its contents spilled into the river: a case of toilet paper bobbing on the surface, paper plates and bowls, other items deemed critical for our comfort and/or survival. I thought about the other thirteen people on the trip and how they would manage to make it through the next week without toilet paper. Then one 2 ½ gallon container of water, then another, lost to the river (we were later able to recover one). Equally disheartening was the loss of first one twelve-pack of India Pale Ale, and then a six-pack. The canoe threated to capsize, but I was able to keep it upright through pressure on top of a buoyant cooler.

I began to consider our options. We had no ability to influence the path of the canoe. None. We could abandon the canoe and our gear and swim to the river’s edge, but the damned tamarisk would keep us from safety unless we were extremely lucky. Fortunately, the other eight in our party had found a good-sized sandbar where they would wait out the weather and wait for the rest of us to catch up. They knew we had experienced trouble as a yard sale of our supplies floated by.

Then around a sharp bend we saw them and they, us. We happened upon them so quickly, they almost couldn’t react in time. Quick-thinking Rick had a throw bag, (a weighted bag attached to a long rope) and threw it too us, but we couldn’t reach it, and were almost out of reach. With Ellen’s help, Kurt dove into the water and heroically got the rope to Chalmers, who tied it to the stern of the boat. In a true team effort, they were able to drag the canoe upstream to the safety of the sandbar. Meanwhile, Jim had snagged Becky and Pat’s canoe and had them moored to the sandbar.

The next few minutes were a bit of a blur. I don’t exactly remember how our gear got out of the water and onto land. I do know that Ellen and Pam helped Chalmers and me out of some of our wet clothes and had found some dry ones (thanks to Rick, I had his quilted fleece). We hung our river-soaked clothes and my sleeping bag over tree limbs to dry. Nothing I brought stayed dry, but my phone did survive the river in my pocket.

We scrounged together some lunch, although it was mid-afternoon. The planned pulled pork was lost, of course. We then had a debate what to do next. Some thought we could simply camp where we were on the sandbar. But it was too small, and also eroding under our feet. There was a clearing nearby, but the tamarisk was guarding it. We knew from our maps and the experience of Rock, Rick and Denis that there was a campsite on the other side of the river not far from our position. The wind was still blowing and no one was anxious to get back into the canoes. But then a weird and funny thing happened. A group of three or four canoes paddled down the river, totally nonchalant and having a good time, not a care in the world. If they could do it, so could we.

We rearranged some of our canoe partners for the tricky trip to the campsite. We split up Pat and Becky and Pam and Ellen, assigning Rock, John, Rick and Jim (or some combination like that) to accompany the others. We made it to our campsite without incident, and setup camp – greatly relieved we were on dry land. A cocktail or two took the edge off. As it turned out, dinner was my responsibility that evening. It was good; we had grilled lamb skewers with tzatziki sauce on pita bread, accompanied by a big Greek salad that Becky helped make. The baklava I brought was somewhat soggy from the river, but we dried it over the grill and it was acceptable. All in all, a good ending to a very extraordinary day.

Becky and Pat earned the respect and admiration of everyone in the party for the way they handled such adversity uncomplaining and with courage and grace.

Day Two was officially a “Red Flag Day,” meaning authorities deemed it dangerous to be on the water. But I’ll not fault Denis or question his decision to go on the river. After all, we had to be at the pickup point several days hence and most of those on the trip were skilled, strong and experienced. But when the weather worsened there was little to do but tough it out. Because, unfortunately, there were few places on the river appropriate to hang out and wait for the weather to improve. The tamarisk.

Part Three will be coming soon.

Great replay of the events as they unfolded on your challenging second day on the Green. So looking forward to part Three!

Love your writing!

I am the older brother of your group newbie, Paul.